️ Notes on Notes

Making a Leslie Rotary Speaker

I have been playing more B3 Organ lately in gigs and I was wondering if there was a cheap small rotary speaker I could get.

The answer is no. I think there is a market for one.

I am really inspired by this genius design.

I also found this awesome half moon switch a guy sells on Ebay. It could probably be altered to use with this design.

Parts List #

3D Parts #

- 3D Parts on Thingaverse

- Get them printed at PCBWay

Hardware #

- 2x 608 fidget bearings 608 Steel Ball Bearings

- 8mm bolt

- 8mm nuts

- 3mm elastic cord

- Make a box out of plywood

Motor Circuit #

- Nema 17 Stepper motor

- TMC 2208 Driver chip

- 100uF+ for 12V Filter Cap (for the 2208)

- 555 Timer chip

- 12V Power Supply

- 7805 5V regulator

- 1000 uF for 5V

- resistors/potentiometers

- TRS 1/4" Sockets

Foot Switch #

- 2x foot switches (double pull double throw switch) DPDT Latching Switches

- 3x 3mm red leds

For simple switch (single pull double throw) to toggle high and low

Half Moon Switch #

Proposed changes to the Robothut design #

Make the foot pedal use a standard 1/4" TRS Balanced cable for the speed control. This is what the Nord half moon switches use.

Would need to modify the foot pedal 3D design to accommodate the TRS input socket. And wire the control board outputs to the 1/4" jack.

Could also put an optional rocker switch on the speaker box.

I would also love to be able to adjust the speed with some knobs. Slow, Fast, Decelerate, Accelerate.

Music Is a Game

A game is a structured form of play

Music is a game. There are rules. It can be played by oneself or with others. What are the rules of the game?

To me, music is like a big puzzle. Whenever I hear a new piece of music, I start trying to put it together.

Is it similar to something I have heard before? How is it novel?

When I get stuck, is there something I don't understand about music that prevents me from putting it together?

Play is the work of childhood.

— Jean Piaget

My son loves to play the piano by ear. I try to make a fun game out of it. When we hear a new song or a cool movie theme, I ask if he can play the melody by ear. If that is easy, I then try to see how far I can push him.

Can you play it in another key?

Can you add chords to it?

What about these chords instead? I might throw in some spicy jazz chords. He either responds, 'No, Dad, that is too weird' or 'Cool, how did you do that?'

At some point, I reach a limit to what he is willing to put up with. The game either gets too hard, or he gets tired of it. Each time we play the game, he gets a little better.

Stay curious.

Failure Leads to Success

Sometimes your biggest failures can lead to your success. If you let it.

That which we persist in doing becomes easier to do, not that the nature of the thing has changed but that our power to do has increased.

— Ralph Waldo Emerson

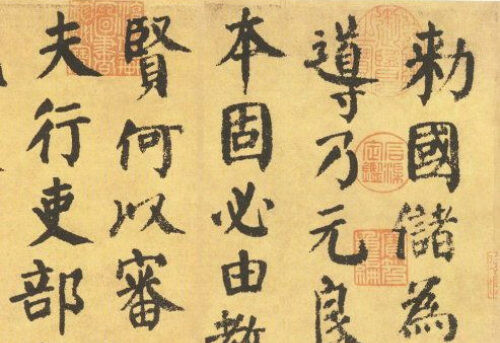

I am reminded of this story about a famous Chinese calligrapher and scholar, Yan Zhenqing (顏真卿), who lived during the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD).

Yan Zhenqing was born into a poor family, but he was ambitious and had a strong desire to succeed in the imperial examinations, which were the gateway to government positions and a prosperous life during that time. However, he failed the exams multiple times, leading to great disappointment and frustration.

Feeling defeated and devastated by his repeated failures, Yan Zhenqing returned home and immersed himself in self-study and self-improvement. He focused on calligraphy and literature, determined to excel in these fields even if he couldn't succeed in the civil service exams.

Through relentless practice, Yan Zhenqing's calligraphic skills improved. He developed a unique style that became highly admired. Eventually, his calligraphy gained widespread recognition, and he became one of the most celebrated calligraphers in Chinese history.

His dedication and perseverance did not go unnoticed. After some time, Yan Zhenqing's talent and accomplishments caught the attention of the Tang court. He was offered an official position, and he eventually served in important government posts, showcasing not only his calligraphy skills but also his scholarly knowledge and administrative abilities.

Yan Zhenqing's story serves as an inspiring reminder that failure is not the end; it can be an opportunity for growth and self-improvement. His journey from exam failure to becoming a renowned calligrapher and successful scholar has become a symbol of persistence and dedication in Chinese culture.

I've had moments like that. I auditioned 3 or 4 times for the university orchestra concerto competition before I won. Each time I competed I learned something about myself. I watched the other performers and figured out why the winners were chosen.

Biotensegrity

Alan Fraser really got me into the idea of the body as a tensegrity structure.

How do the bones, tendons, and muscles work together?

When I think of good movement, I think of great athletic performances of discuss or javelin throwers. There is an elasticity and power through the whole range of motion.

Biotensegrity is a concept that combines the words "biology" and "tensegrity" to describe a structural principle found in living organisms, including humans. Tensegrity is a term derived from "tensional integrity," which refers to a structural system where isolated components are held together in a stable form by a balance of tension and compression forces.

In the context of biotensegrity, the body is seen as a tensegrity structure, where bones, muscles, ligaments, and other soft tissues work together to create a stable and efficient system. This is in contrast to the traditional mechanical model of the human body, where bones are viewed as the primary load-bearing structures, and muscles act only to move these bones.

Here are some examples of tensegrity structures:

Biotensegrity suggests that every part of the body is interconnected and interdependent, and changes in one area can affect the entire structure. This concept is especially relevant in understanding how the body maintains its shape, balance, and structural integrity during movement and physical activities.

So how does this apply to piano technique?

Is the focus fast playing or is it smoothness, connectedness, elasticity? What should good playing feel like?

The quality of the movement matters.

Isolate Create Imitate

Here is a framework for learning.

Isolate

Be very specific about the thing you want to improve and work on.

This could be a blues lick, a jazz voicing, or a passage from a piece you are learning. For the example here, let's say we are transcribing a blues solo and there is a lick we like. We isolate this blues lick.

The more specific you can be about what needs fixed or what you are trying to improve the better your progress.

Create

Once you isolate it now create variations on the thing. For the blues lick, how many different ways can you play it? Does it work for other chord progressions? Can you sing it?

If you practice the same thing over and over eventually the brain starts to tune out. If you create something with it you will stay engaged and discover new things.

Another way to say it is that you integrate the material.

Imitate

Still using the blues lick as an example, now go back to the recording. Can you make it sound just like the blues artist? Are there similar variations of this lick that you could isolate? After listening some more, does it inspire you to create something else?

These 3 areas feed on each other. I find this framework leads to an enjoyable and productive practice session.

This doesn't just work for jazz. If I were working on a classical piece and I am having trouble with a difficult passage. I go through the same process.

Isolate the passage. Be very specific about what makes the passage difficult. Is it a fingering? Is it the counterpoint or the harmony?

Then I create variations on the passage. Is there an easier way to play it? Meaning, can I simplify or change the notes to something else that is easier?

One common way to do this is practice hands alone. This isolates the hands. But you could go further. Can you simplify the left hand to something easier? Can you sing the melody in the right hand as you play the left hand? Can you play a simplified block harmony in the left hand (or with both hands) while singing the right hand? If it is a large leap can you double the leap distance and do that? How about make the distance smaller and do that? The variations are endless.

Then you could find great players playing the passage. Watch them or listen to them. Your teacher might also play it for you. This is the imitate phase.

This process of Isolate, Create, and Imitate is not linear. Just like learning is not linear. It is much like trying to reach your destination by wandering through a strange forest. The adventurer gathers items and friends that will help him along his journey. What you find might be unexpected and surprising.

Will A.I. Replace Musicians?

I doubt it. Here's why.

Will it replace writing?

Some writing, yes. What kind of writing will it replace? ChatGPT can reasonable churn out a respectable college or HS essay that would get you an A in a class but would it be the kind of writing that people would actually want to read?

Good writing is not just well formed sentences regurgitating the aggregated information from the internet.

What are the qualities of good literature that have lasted the test of time?

Why read Emily Dickinson or Victor Hugo or Shakespeare? Could an A.I. generate such works? A.I. can only look backwards not forwards.

I have yet to hear a piece of music generated by an A.I. worth listening to that hasn't had some heavy direction and guidance from a human. And maybe that is the point. A.I. will become a tool just like music notation and recording technology.

Technology has always had a dramatic impact on how we make music. From the invention of instruments like the piano to music notation software to recording technology to social media.

Has recorded music replaced live music making? Maybe in some circumstances. You can hire a D.J. instead of a live band. But it still isn't the same. Dancing to recordings is still not the same as dancing to a live band.

A machine can throw a discuss far greater than a human can, yet we still watch the olympics and enjoy seeing humans throw a discuss. A machine can go faster than a human can run, yet we still have foot races. There is a human component of music making that can't be replaced by a machine. A human breaths, feels, thinks, makes mistakes, is unpredictable. An A.I. is none of those things. It's a tool.

Hand Independence

Especially for beginning pianists, hand independence with articulation is tricky. The temptation is to do the same thing in both hands.

Here is a simple exercise to practice this. Be sure to not break the slur in the slurring hand.

I think it is a cross brain thing. It is hard to do different things in each hand.

And then for a harder challenge try switching between the two like this.

Why I Hate Hanon

Hanon has been a staple in piano technique.

Why?

The russians would practice the exercises in all 12 keys at ridiculous speeds.

Is there a better way?

I'm not a fan of exercises for their own sake like Czerny or Hanon. I find them dull and boring and wastes a lot of time.

The biggest problem I see for most musicians is that finger dexterity is not their limiting factor. There are so many skills like rhythm, music theory, phrasing, and note reading. Time would be much better spent working on those skills. Especially in the early stages of learning.

Even today, I don't ever see the need for myself to practice Hanon. If I want to work on finger dexterity why not work on a Chopin or Moskowski etude? They will accomplish similar goals but will also teach you music and phrasing.

Instead, why not work on real music? It is much more enjoyable and engaging.

Dealing with Overwhelm

When learning a new skill or starting a new project it can be easy to get overwhelmed. I have to remind myself that Rome was not built in a day.

It is better to take a small action, even done poorly, than to get overwhelmed and take no action at all.

The best time to plant a tree is 20 years ago. The next best day is today.

Becoming the Fool

If you are not willing to be a fool, you can't become a master.

— Jordan B. Peterson

Every time I approach the piano I try to do so with some curiosity and humility. There is always so much to learn and things to work on.

As far as I have come, I have that much further to go.

The more I learn, the more I realize the less I knew.

There are two things you can do with this idea. Either it feels futile and I will never "get there" and achieve mastery.

Or it is an exciting road of endless possibilities and things to explore.

Knowing and Hearing

When playing by ear there are 2 aspects. You play what you know and/or you play what you hear.

Let me explain.

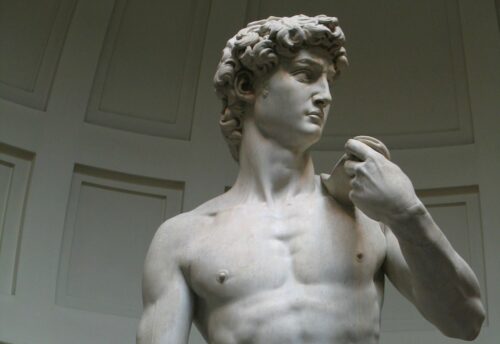

This is very much like artists.

Artists go through many years studying anatomy to draw the human figure. They study the skeleton, the muscles, the tendons. Even though they know all this anatomy, when they do a work they will still often use a reference.

They draw what they know combined with what they see.

Likewise when I am improvising, composing, or transcribing, I play what I hear and what I know. When I am transcribing I can make good guesses based on what I know about theory.

What key is it in? What scales might they use? Does this sound like something I already know?

This is why folks with perfect pitch are not always the greatest musicians. They can hear great but they lack the knowledge. The two concepts are tightly related. Not quite the same. But not quite separable either. Much like the eastern duality ying yang symbol.

The light is inside the dark. The light also leads to the dark and the other way around. Strengthening you ears will lead to greater musical knowledge. Having more knowledge will also lead to better ears.

Before You Feel Ready

If you wait to perform a piece until you feel absolutely ready, you might not every get there.

To achieve great things, two things are needed: a plan and not quite enough time.

— Leonard Bernstein

Much like other things in life, perfectionism is really an excuse to not take action.

Very often you will fail your way to success.

Here is what I mean. When I was preparing to play Liszt's Totentanz with the university orchestra I scheduled myself a bunch of mini performances during the learning process for friends or whoever would listen. Some of these performances were awful but I learned what I needed to fix. I performed the piece when I didn't feel completely ready. When the real performance came I knew how I would respond under stress and I had the confidence to succeed.

Learning theory also concludes that memorization and learning work best if we test our learning before we are ready. For example take the quiz before the lecture. Even if we guess the answers or don't know at all. We then study and we are much more engaged to figure out the answers we missed. See my reading list.

I often do this with my students. I have them play their piece memorized before they feel absolutely confident they can do it. In the process of guessing some notes and making some mistakes they see where their holes are.

The usual path for students is the play their recital piece to infinity until there is no chance for mistake.

The problem with this approach is that the memory is often very fragile. It is only finger memory and they haven't engaged the brain to put it together.

Effective Practice

- break down the problem

- interleave practice — mix practicing different types of tasks (e.g. transposing, rhythm, ear training, singing, …)

- don't always start at the beginning — be able to start from the middle or end

- define the problem — you can't fix what you can't define

- create new exercises that are easier or similar to the problem being practiced

Creative Practice

There are thousands of ways to practice one skill. For example, say you are practicing a new blues lick. How many ways can you devise to practice the lick?

- transpose it

- vary the rhythm

- change the notes

- change it from major to minor (or some other weird scale like octotonic/diminished or whole tone or bitriadic)

- sing it

- harmonize it (play a counter melody while you sing it, grab a partner and make a duet)

- play it in different styles (bebop, slow blues, up beat blues, rag time, New Orleans, Funky, George Shearing chords, McCoy Tyner 4ths, Red Garland 4-note-rootless+octave-melody)

The Birthday Party

I was attending a birthday party with a bunch of piano majors. Whether from lack of confidence or skill, I don't know which, when it came time to sing Happy Birthday, no one volunteered to sit down and play along.

The sad embarrassment is that most classical musicians do not play by ear very well. I know many teachers that actively discourage it.

Playing by ear is a skill like anything else.

Practice Time

The best musicians I know don't practice compulsively. They don't lock themselves in a room and practice 10+ hours a day.

Their practice is focused and intentional. And there is a minimum amount of time one needs to spend at their instrument to master it.

The sweet spot seems to be about 3 hours a day. This is the time suggested by Jascha Heifetz. I have also observed this time in others (and myself) as well.

But it is not time alone that makes you great. I routinely saw piano majors at university spend 5+ hours a day practicing but they didn't get better. A lot of their practice time was to log hours and to play concerts for themselves.

What does effective practice feel like?

Standout Performers

When I judge a piano competition for several hours there are usually several performers that stand out from the rest. I most often judge competitions for state solo & ensemble or regional talent shows. Here are some of the qualities of the performers that stand out:

- stage presence

- technical mastery

- piece selection appropriate difficulty for the skill level

- response to mistakes (Can they recover from a mistake?)

- All mistakes not created equal

- gracious acknowledgement of the audience

- knowing your competitors

- knowing the judges

Knowing your competitors

When competing it is valuable to know what you are up against. If a competition is held annually it is excellent feedback to watch the rest of the competition after you compete. I remember doing this for university concerto competition. I didn't make it the first couple of auditions but I watched all the other competitors. I got to see which auditions made the cut and what kinds of pieces and performances the judges picked.

Knowing your judges

Sometimes this is not possible, but for recurring competitions where you can guess who the judges might be you might be able to guess what kinds of things that judge is looking for. For example, I knew that no matter how well someone played Gershwin or Beethoven the university conductor didn't really like doing those concertos. Picking Liszt or Saint-Saens or Grieg was a much better choice.

Practice the Hard Stuff

You get better at something by practicing the things you are bad at, not the things you are good at.

So often piano practice turns into a concert for oneself. Just playing the things you are comfortable with and getting the feeling you are making progress while not actually getting better.

There is this study with a baseball team learning to bat. They split the team in half for practices. One group the batters were pitched random pitches. Curve balls, fast balls, …

The other half were consistently thrown one type of pitch for a session.

Which group got better? Which group felt like they got better?

The random pitch group didn't hit as many balls in practice and they felt like they weren't making progress. But in the games their hitting improved.

The same pitch group felt like they were getting better because they could hit a lot more balls in practice. But in reality this group didn't get any better in a real game.

Several lessons here.

Make practice match the end goal (i.e. perform better at a game).

Real progress can feel really slow and at times frustrating.

Are practice session a vanity project or are they serving their purpose to acquire skill?

Mistakes Not Created Equal

When I listen to someone play and they make a mistake, what is the cause of that mistake?

Is it memory?

Or is it lack of understanding?

Lack of technical mastery?

When I am judging a piano competition and a pianist messes up a spot invariably it is in a harmonically complex part. At any point in the piece you should know what key you are in and what chord you are on.

When students see the notes they play as a collection of random notes it tends to lead to certain mistakes than someone who understands the harmony would never make.

This reminds me of the chess study.

Chess Study

One of my favorite studies on learning and expert skill is a study done with chess experts.

They gathered a group of chess experts and novices and showed them a chess board on a projector. The researchers then turned off the image and handed them a chess board and a box of chess pieces and had them recreate the chess board shown them previously. The more expert the player the better they were able to recreate the board arrangement.

Now here is the interesting bit.

They then showed that same group random arrangements of chess pieces on the board. With this random placement the experts were no better than the novices at recreating the board.

The first images shown were valid chess arrangements from actual games.

What does this mean?

It means that what we commonly call memorization really reflects an understanding of patterns.

In music, some musicians can "memorize" and "learn" music faster than others. I believe what this shows is the musician's skill at understanding the patterns. Music is not random. The chord pattens follow some common patterns.

This is also true of improvisation. A good improvisor understands the patterns and rhythm to make something up. The improvisor isn't making up random stuff no more than speaking language is making up random sounds.